- Home

- Elena Chudinova

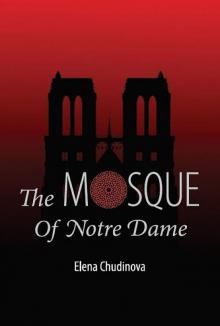

The Mosque of Notre Dame

The Mosque of Notre Dame Read online

THE

MOSQUE

OF

NOTRE DAME

By

Elena Chudinova

THE MOSQUE OF NOTRE DAME

BY ELENA CHUDINOVA

Original title:

Елена Чудинова

Мечеть Парижской Богоматери: 2048 год

© Чудинова, Е., 2006

Translation (as Notre Dame Mosque in Paris: 2048 )

by Snežana Ivanišević de Berthet

© 2015 The Remnant

American edition edited

by Duncan Maxwell Anderson, 2015

TABLE OF CONTENTs

Introduction

Zeynab’s last shopping trip

Valerie

Slobodan

Confession without a confessional

Sophia

Ahmad ibn Salih

The price of intimidation

Annette’s awakening

The road through the darkness

The house of the converts

An underground camp

The house of the converts (continued)

The path of the skeletons

A conference under ground

A plan

The barricades

The barricades (continued)

The lull

An attack within an attack

The ship is sailing

Introduction

to the American Edition

I am very happy to introduce my book to American readers. This year The Mosque of Notre Dame turned ten years old. So far, it has been published in Russian, Serbian, Polish, Bulgarian, Turkish, and French, and translated into Norwegian. I find it hard to express my appreciation to all the novel’s friends and supporters, whose selfless efforts have made it possible for the book to reach countless new readers around the world.

Still, I am sometimes enveloped by a sense of gloom. I am terrified that we are losing precious time. The danger described in The Mosque of Notre Dame grows every day.

I began writing this novel after the fall of the Twin Towers in 2001, but before the mass murder of schoolchildren in the Russian city of Beslan by Islamic terrorists in 2004. Do most Americans even know about the horrible tragedy of Beslan—those three days during which all Russians sat, glued to their television screens, praying? Chechen Muslim terrorists had attacked a village school and kidnapped more than 700 children, imprisoning them in a stuffy gymnasium built to accommodate 100 people. Before the suspense and horror ended, 333 people, including rescuers, were murdered. Half of those killed—186 of them—were children as young as 9 years old.

If facts cannot be silenced, they still can be distorted. Do Russians know about the fall of the Twin Towers? Definitely. But how many bizarre Russian versions of this event have I heard over the years, according to which the Towers were toppled by “non-Muslims”? For some reason, someone is very interested in preventing discussion about the threat to our civilization posed by Islamic occupation.

The character of Sophia, the principal heroine of my novel, appeared in my imagination after I read a news story about a twelve-year-old Russian girl, the daughter of a businessman, who was kidnapped by Chechen bandits. The girl was held for more than six months and was tortured and abused. To speed the father’s ransom payments, the kidnappers cut off two of her fingers. Eventually, the girl was rescued and the kidnappers arrested.

An American offered to pay for the girl’s rehabilitation at a U.S. clinic—since all her family’s resources had been spent on her ransom. But the rescued girl was refused entry to the United States by the State Department. Strangest of all, the story of this poor, wounded girl being barred entry by the usually generous U.S. government went virtually unreported in America’s news media.

It is worth noting that, at the time, many people in the West had been making excuses for the Chechen criminals. So perhaps it was inconvenient that, unlike mere words, a maimed child’s injuries offer incontrovertible evidence of the depravity of the people the Western press likes to call Muslim “militants.”

A thought crossed my mind: If there is no justice in this world, will this girl seek vengeance when she grows up? As it turned out, she chose another, better path. That is why I do not mention her name. But as the story develops in my novel, the heroine chooses vengeance—a lonely, bitter path.

Most of the large-scale events the book describes have not yet taken place in our world. The European Union has not turned into Eurabia — so far . For now, vineyards have not been cut down. The great paintings of Western art have not been burned. And the magnificent Cathedral of Notre Dame has not been turned into a mosque. But how the year 2048 will turn out for Europe and the West depends on us.

This book must be read today, because tomorrow may be too late.

Elena Chudinova

Calvados, France - Moscow, Russia

IV August

Anno Domini MMXV

CHAPTER 1

Zeynab’s last shopping trip

Eugène-Olivier walked down the Champs-Élysées as fast as his uncomfortable clothing would allow. He certainly was not running—someone running would only draw attention. But his pace was faster than if he had been running. Besides, few runners could run for six hours without a break. Eighteen-year-old Eugène-Olivier could walk all around Paris this way without stopping. It seemed that he had just passed through the Jardin du Luxembourg when already, the Bridge of Invalids was also behind him and the Champs-Élysées sparkled right and left—from lights in store window displays and through the draped windows of private residences. There were not many residences in the Champs-Élysées; there were many more stores like the one he was now approaching.

* * *

Zeynab set out from her house on foot. She had never heard the word “Impressionism” in her life. Thus the play of gold and blue light that bathed Paris that sunny afternoon in early spring could hardly have inspired her imagination. It was pleasant, but not nearly so pleasant as the fact that her husband did not limit her shopping expenditures. And today there was going to be a fashion show in the women’s department of the big department store on the Champs-Élysées.

It was not quite right, of course, for her to go to the store alone, but even the Religious Guard closed its eyes to the fact that this rule was regularly violated in the richest neighborhoods and in the poorest. With the poor, all the men in the family had to work while the women rushed around from store to store looking for a cheaper piece of mutton.

In the rich neighborhoods, if you couldn’t disregard the rules others were obliged to follow, what would be the pleasure in being a man of influence? Even the Religious Guard understood these fine points. Only ordinary people were not exempt from following the rules.

Of course, it was always best to be prudent. For example, Zeynab went shopping alone—but Qadi Malik would later pick her up from the store, so in a sense she was simply going to meet her husband.

Zeynab had only crossed from the Quai d’Orsay over the Emirates Bridge and onto the Champs-Élysées, when she stopped.

Translucent rainbows flashed on the window displays, drawing attention to three-piece suits of soft black wool, light-colored suits of silky linen for seaside vacations, snowy white silk poplin and thin linens, colorful polo shirts, cashmere overcoats, Moroccan leather shoes next to curved ivory shoehorns, tie clips and pins, hand sewn neckties, heavy bracelets of Swiss wristwatches, rings and gloves, engraved and gem-encrusted canes—simply everything a man could wish for.

The ladies’ department, understandably, was invisible from the street, its treasures hidden behind reflective glass, hidden like Ali Baba’s cave. Zeynab did not hurry in to see them as

usual; she was enjoying the fine weather. When she was finished, she would have to call Malik on his cell phone. And with him she would observe the glory of the spring day from behind the closed windows of the Mercedes. The windows of the Mercedes were tinted, of course; you could stare as much as you liked and no one would look back.

What a beautiful day! Not even the poor, whining incessantly over their begging bowls, managed to annoy her, nor did the piercing whistles and loud screams of children playing. Soft pies shone white in the hands of street vendors and passed in the blink of an eye into the hands of buyers. Loose couscous sparkled as it leapt from the boiler into small paper bags. Flies greedily circled above the baklava and Turkish delight, as customers in street cafes alternately sipped steaming black brew and ice water. How beautiful the Champs-Élysées was in spring!

For some reason, everyone seemed to be hurrying toward the Arc de Triomphe. How interesting, what could be going on there?

Eugène-Olivier stopped so suddenly in front of the neon sign of the department store that he almost knocked over a pudgy woman. This was bad, very bad—he hadn’t calculated the time properly. Whoever arrived too early could also arrive too late. Sevazmios always appeared everywhere on time, to the minute.

For as long as Eugène-Olivier could remember, the square around the Arc de Triomphe had been a pedestrian zone for public celebrations. But now they had begun to build something. A dozen metal containers similar to those used for garbage had been placed around the Arc at equal distances. The container on the right was filled with stones, and to the left of the container there was a small truck with a trailer.

A car moved slowly across the pedestrian square, a green police car with a trailer for the transportation of prisoners. Eugène-Olivier became cautious—but then checked himself and relaxed. The invisible statistician who lived inside him reminded him that he should not concern himself today with anything out of the ordinary. No matter what happened, he should only think about his orders. He wasn’t even curious; he was just pretending to pass the time.

Eugène-Olivier turned his attention to the barred back door of the car that was moving through the crowd at a snail’s pace. Behind the door there was a man. The green pick-up slowed down. Why had they brought this poor wretch here? There was no prison or courthouse.

Only now did he notice the fresh posters glued to the walls of the Arc and the round pillars. O, how he hated to read their worm-like letters! But he didn’t have to, because an Arab sitting on a bench had just unrolled a poster and prepared to read it out loud to the crowd of gathered children and women. Maybe I should pretend I can’t read, either, thought Eugène-Olivier, pushing his way through the crowd.

“He undermined the obligations he undertook upon accepting work,” read the grinning Arab.

“What exactly does that mean, Mr. Hussein?” asked a tall woman in a blue chador.

“The giaour promised, Aunt Mariam, that all the grapes grown on his land would be delivered to the fruit drying plant,” explained the Arab patronizingly. “And he also gave false information. He blamed spillage and frost when, in fact, he was hiding grapes. And you can imagine what he was doing with them.“

“Don’t tell me was making wine? Oh, the beast!” The woman clapped her hands.

“Dog!”

“Infidel dog!”

“We’ll show him wine! Dog!” shouted the children.

The police brought the prisoner out of the car. He turned out to be an older man, but still feisty, full of strength—judging by his walk and his still-fresh, tanned face. He was thin and wiry, with iron muscles that rippled under his flannel shirt. His baggy denim overalls were so faded that they looked almost white, and his gray cap was so burnt by the sun that it was difficult to discern the advertisement of some sports competition banned long ago. He was a farmer, it was obvious at first glance, even if one did not know that he was a winemaker. But where were they taking him? To some stupid concrete pillar right under the Arc that hadn’t been there for long.

“Kiamran, hey, Kiamran, it’s about to start!” A young man in a colorful shirt, obviously drugged, went up to the metal container and began to take several stones the size of apples in his hands. Maybe he thought they really were apples. His eyes were completely white.

Holding the stones with his left hand to his chest, he continued to take more with his right. He bent over awkwardly and a stone fell on his foot. Instead of screaming in pain, he stopped and smiled to himself, as if he had heard a joke.

“Leave them, you have enough already!” the woman in the blue chador told the young man. She raised the folds of her chador like an apron and began to gather stones in it.

Behind her two other youths were already hurrying to fill their pockets; a younger, chubby one who held his cigarette in his teeth to free his hands, and a very little girl whose face was uncovered.

Was it possible that they were all drugged?

Eugène-Olivier had considered himself a soldier since the age of eleven and strictly speaking, that is what he was. For that very reason he wasn’t afraid to honestly admit what another person might have tried to describe less specifically: he was afraid.

The answer was like a ball that refused to go into the basket. It was so obvious, so simple, that he saw it but didn’t want to understand it. Calm down, weakling. You have to get a grip on yourself...

Zeynab hesitated. She wanted to take some stones, too—she could wipe her hands later with the wet, scented napkin she always carried with her—but what would happen to her manicure? She hated to ruin it; she had put on this nice polish only yesterday! Really, they could offer people of position the opportunity to buy something more practical. Or at the very least wrap the stones in clean plastic wrap. Her husband was right; they whined for social assistance and complained there were no jobs, but when they needed to make a little effort to earn some money, all they could think about was entertainment.

But the poor woman (who really had no business being in that fancy neighborhood in the first place) had armed herself so well with stones that Zeynab couldn’t resist. Oh, so what if the manicure was ruined? She could touch it up in the ladies’ room of the department store, and the manicurist would come again tomorrow anyway.

The policemen were already taking out special handcuffs to rivet the old man to the post. Eugène-Olivier understood everything now, of course, before he forced himself to go back to listening in on the crowd. Completely calm (he had already seen quite a bit in his eighteen years), he was standing thirty feet from the condemned man when something extraordinary happened.

Freeing his hand from behind his back, the farmer suddenly raised his chin and seemed to nod his head with dignity, bringing his cuffed hand to his forehead, which he touched lightly with his fingers before gently bringing his hand down to his stomach, and from there to his left shoulder and then to his right.

The old man crossed himself!

It was like a signal. The policemen barely managed to rivet the farmer to the post before fleeing.

“Bismilla-ah!”

Several stones missed, and then one hit the farmer in the face and started a trail of blood. It was impossible to make anything out after that. People were shouting, whistling, laughing, as the stones flew and fell like hail on the asphalt.

“Inshall-a-ah!”

“Death to the kafir!”

“Death to the dog!”

“Death to the winemaker!”

“Subhanalla-a-ah!”

Eugène-Olivier suddenly noticed a little boy in a fluffy little white outfit, not older than three, with light chestnut curls, who moved confidently on chubby legs—in his hands was a stone.

“And what are you saving your hands for?” A young man in a black shirt, apparently less drunk than the others, approached Eugène-Olivier. Probably one of the volunteers of the religious guard. He needed to get away.

The revelry of the crowd did not last longer than fifteen minutes, and died out quickly. The bloodied body

hung helplessly on its chains, the stones knee-deep. He had probably died before the stones stopped flying.

Zeynab wiped her hands with a jasmine-scented towelette. She had broken a nail after all, but the manicurist would be able to glue on a piece of plastic that would be invisible under the polish.

Eugène-Olivier slipped silently out of the crowd. Another image of their lives, just another among dozens like it. Another death, just one of thousands of deaths. What was so unusual about that?

As long as the vineyards of France were alive, there would be winemakers, and there would be a black market. And they couldn’t cut them down because they loved raisins; it seemed they couldn’t make any dish that didn’t contain them. And as long as there was a black market, they would hunt down wine sellers and winemakers, and publicly torture them to death, according to the sharia . Nevertheless, there was something that fascinated him, something very important. Wasn’t that the magnificent sign of the Cross, the wide swing, the five fingers transformed into the symbol of the five wounds of Christ? Were there still believers? But twenty years had passed since the last Mass was celebrated!

Eugène-Olivier did not believe in God for family reasons. The Lévêque family, which had occupied a house in peaceful Versailles for a good ten generations, was once a part of the ruling class.

“We are, of course, plutocrats,” Grandfather Patrice used to say. He had a sharp tongue.

“Other authorities in the Republic do not exist. But your golden calf, in any case, is an aristocrat. The Liberals have demonstrated their cleverness with triple security and electronics, like the CIA—and for what? So that an auditorium of one hundred teens jumping to the sound of rap can’t be infiltrated by the one-hundred-and-first, who isn’t on the list? Let them go ahead and laugh. The purpose of the market is matrimonial. We won’t mix our blood with new money, even if they have more of it than we do.

The Mosque of Notre Dame

The Mosque of Notre Dame